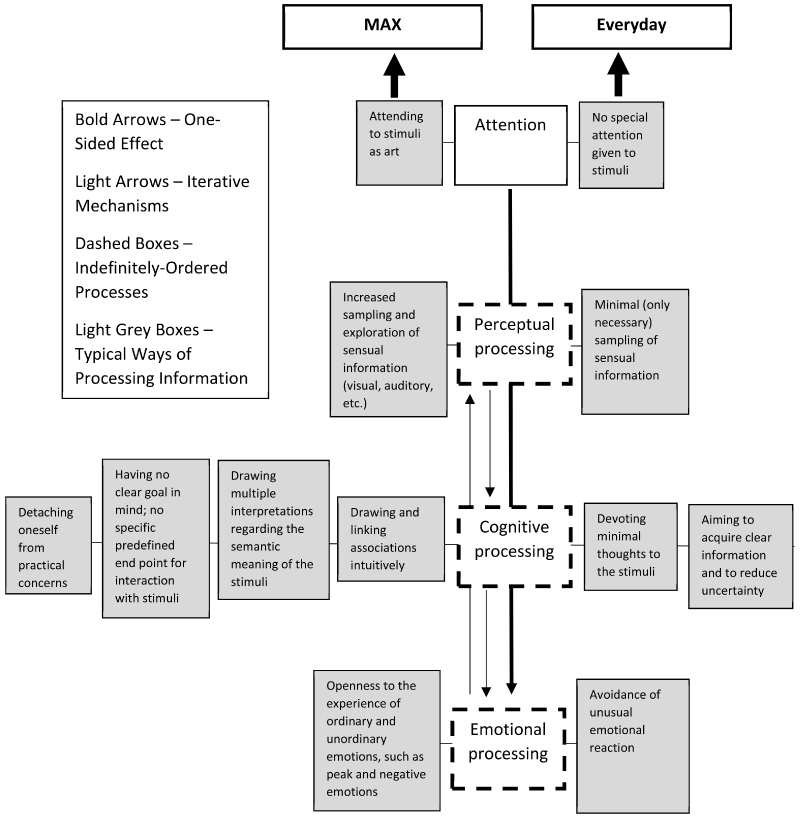

Experiencing art calls for a unique processing mode – this premise has been repeatedly debated during the last 300 years. Despite that, we still lack a theoretical and empirical basis for understanding this mode essential to understanding experiencing of art. We begin this position paper by reviewing the literature related to this mode and revealing a wide diversity and hardly commensurable theoretical approaches. This might be an important reason for the thin empirical data regarding this theme, especially when looking for ecologically valid experimental studies. We propose the Mode of Art eXperience (MAX) concept to establish a coherent theoretical framework. We argue that even very established works often overlook the essence of more profound and so to say “true” art experience. We discuss MAX in relation to evolutionary psychology, art history, and other cognitive modes (play, religion, and the Everyday). We also propose that MAX is not the only extraordinary mode to process information specifically, but that for experiencing art, we evidently need a frame that enables MAX to unfold the full range of art-related phenomena which make art so culturally particular and essential for humankind.

Itay Goetz, Claus Christian Carbon, "The Art of Experiencing Art: On the Nature and the Origins of the Mode of Art eXperience (MAX)" in Journal of Perceptual Imaging, 2023, pp 1 - 19, https://doi.org/10.2352/J.Percept.Imaging.2023.6.000403

| Concept | Authors | Short Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Mimesis | Plato (375 BC) | Viewing objects represented by artworks in a dream-reality state. Acknowledging that the objects represented are appearances rather than real objects. Forming a mental representation of the depicted objects in mind by freely combining real outside-world and imaginative information. |

| 2. Disinterested attention | Shaftesbury (1671–1713/1961) | Approaching objects identified as aesthetic solely for the sake of their perceptual experience. Devoting complete attention to them, with curiosity to what is foreign and external to oneself, and with no aim to fulfil self-interests through them. Not devoting any attention to our preconceptions of the world; these may limit our ability to make true, independent and free judgments of the objects. |

| 3. Aesthetic attitude | Alison [1] | Attending to the object impractically and purposelessly, with no interest other than perceiving it. Being unoccupied by any other objects or thoughts so that one remains open to all the impressions the object they engage with can produce. Embracing these impressions through associative thinking. |

| 4. Aesthetic judgment | Kant [81] | Approaching objects of nature or art purposively without purpose. That is, approaching objects with the intent to derive pleasure from them, but impractically, with no will to possess them, without developing any expectations regarding the experience or the use of them, and by applying only feelings (and not predefined criteria - concepts) to the evaluation of them. This enables the open-ended intuitive generation and linkage of associations, defined as the free harmonious interplay between imagination and understanding in the mind. |

| 5. Non-relational attention | Schopenhauer [114] | Devoting complete attention to the art object, with no concern to its representation (the causal, spatial or temporal relation between its features), nor one’s will (one’s wishes or goals). The artwork becomes one’s whole world and constitutes the only object of interest. It frees the individual, and it is itself a desirable end. |

| 6. As-If, Make-Believe state | Husserl [80] | Approaching the artwork as a paradox. Experiencing it through our senses, as an embodied product of reality on the one hand, and as a window to a fantasy world on the other hand. Thus, treating the artwork as independent from physical reality and from any personal practical concerns. |

| 7. Physical distance | Bullough [22] | Approaching art impractically, detached from the context of one’s needs, and ends by relating to it “objectively”. Interpreting one’s “subjective” affections and feelings as characteristics of the artwork rather than one’s internal world. |

| 8. Art experience | Dewey [50] | Approaching art openly, with no set goal. Actively embracing resistances, tensions and diversions as processing proceeds towards an inclusive, fulfilling, undefined and self-expanding end. |

| 9. Aura | Benjamin [13] | Approaching art easily and in relaxed conditions, but with certain honour and respect. Allowing it to absorb and permeate the self’s state of being yet maintaining emotional and physical distance from it. |

| 10. Aesthetic vision | Tomas [124] | Being absorbed in the artwork and unconsciously suspending disbelief. Thus, perceiving objects represented in a painting as worldly rather than the painted appearances. |

| 11. Liminality | Turner [128] | Stepping out of practical and everyday social and cultural concerns. Viewing the artwork, oneself, and the world with unordinary thoughts and feelings, as in religious rituals. |

| 12. Aesthetic point of view | Beardsley [10] | Actively seeking sources of value within an object by focusing primarily on its formal features. Searching for semantic values in the object and availing of them. |

| 13. [Observer’s] Set | Kreitler and Kreitler [86] | Being open to engaging with objects that vary in their definitiveness, correctness, and subjective value. Searching for personal and emotional resonance within these objects. Approaching them as distinct from other, day-to-day objects. |

| 14. Flow | Csikszentmihalyi [37] | Employing one’s skills to deal with the artwork and the challenge offered by the artist. Engaging with the artwork for its own sake (not for the sake of any external reward), being fully involved in the action and fully removed from the everyday world. |

| 15. Thinking I, Being I | Cupchik [38, 40] | Approaching art on two complementary levels. Through one’s ego: Instrumentally, analytically, and applying relevant knowledge to the stylistic features identified in the work (Thinking I). Through the self’s identity: personally, emotionally, even unconsciously or transcendentally, and through absorbing oneself in the artwork (Being I). |

| 16. Unwilled Attention | Rowe [111] | Being passively and fully absorbed by the object. Not deliberately directing attention towards it, nor wishing or aiming to benefit from it. |

| 17. State of Aesthetic experience | Marković [94] | Being in an exceptional state of mind that is qualitatively different from everyday mental states. Directing attentional resources primarily towards a single object while paying decreased attention to the surrounding environment, the self, and time. |

| 18. Artistic Design Stance | Bullot and Reber [21] | Following the experience of disfluency in understanding an artwork, developing sensitivity to its historical context by inquiring into its means, authorship, and creation. This enables recall of autobiographical and contextual information that facilitates the reasoning about the artwork’s origin, meaning, importance, and results in a better understanding of it. |

| 19. Esthetic mode of viewing | Tröndle et al. [126] | Exploring the objects’ low-level features, which leads to the experience of increased intense physiological, emotional, and cognitive responses to the object compared to everyday objects. |

| 20. Art Schema | Wagner et al. [135] | Being in a safe environment, not concerned with immediate pragmatic goals, ready to explore and elaborate the formal features of the work. Expecting to experience pleasure while being “open” to the experience of a range of emotions and feelings. |

| 21. Aesthetic Attention | Nanay [103] | Focusing attention on one object but distributing it among its features. Freely wandering around the object’s low-level features visually, without any practical concerns related to the object. |

| 22. Information-craving mode | Fazekas [63] | Attention is focused on one object yet distributed across its features. There are no practical concerns or predefined goals involved. Attention consists of the rapid overt sequential reallocation of vision across many different low-level features of the object. |

| 23. Genre Schema | Menninghaus et al. [96] | A more specific version of art schema (see above), in which spectators develop specific expectations regarding the art they are about to encounter based on its genre. This enables spectators to distance themselves from the artwork and more readily embrace its components, as well as their emotions, such as fear, disgust and sadness, freely (in the case of horror or similar genre). |

| 24. Expecting the Unexpected | Muth et al. [101] | Being in an active mode of searching for meaning and self-extending. Embracing ambiguity and semantic instability (SeIns), while defying straightforward information processing, familiarity and security. |

| 25. Aesthetic Attitude | Westerman [137] | Focusing the attention solely on the artwork rather than on information external to it, such as historical or contextual information or one’s personal experience, expectations or desires. |

| 26. Aesthetic Mode | Pelowski et al. [107] | Preparing to engage with art by expecting to feel pleasure. Adopting a detached “aesthetic” focus on form or style without concerns about the object’s meaning, relevance, or use. Being more tolerant of surprise, disgust, and ambiguity. |

| 27. Ecological Art Experience | Carbon [27] | In an art setting (e.g., museum/gallery/fair), individuals attend to artwork openly, often repeatedly, and with physical distance, without searching for ultimate answers or “solutions” to artworks. |

Find this author on Google Scholar

Find this author on Google Scholar Find this author on PubMed

Find this author on PubMed